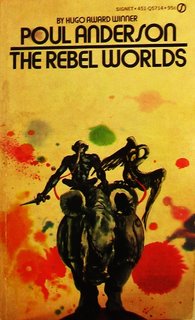

The Rebel Worlds

"Flandry stayed behind a while. No particular girl for me, ever, he reflected, unless Hugh McCormac has the kindness to get himself killed. Maybe then -

"Flandry stayed behind a while. No particular girl for me, ever, he reflected, unless Hugh McCormac has the kindness to get himself killed. Maybe then - Could I arrange it somehow - if she'd never know I had - could I? A daydream of course. But supposing the opportunity came my way ... could I?

I can't honestly say." - The Rebel Worlds, Poul Anderson (Signet, 1969)

Poul Anderson occupies a fairly revered place in the hierarchy of science fiction authors. Unlike many writers whose works are placed on a gold-and-marble plinth in the halls of the genre's collective memory, Anderson isn't enshrined because of heavy intellectual themes, or high-minded seriousness, or - heavens forbid - his philosophy. He occupies a place of honor because he knows how to invent a universe and tell a story - without either collapsing under their own weight.

The Rebel Worlds relates an episode in the mid-career of Anderson's hedonistic clandestine agent, Dominic Flandry (now a Lieutenant Commander), in the service of the vast, glorious and corrupt Terran Empire. Dispatched to prevent or subdue an uprising by a reformist admiral caught in a subtle web of plots and intrigues, Flandry's powers - of persuasion, perception and manipulation - are tested to a high degree of strain, and his task is further complicated when he falls for the admiral's wife, who is the unwitting key to the entire rebellion.

In the hands of an author less instinctive than Anderson, this book (and the entire universe it is based on) might have fallen as flat as the dozens of imitators the Flandry stories have spawned. But Anderson knew how to get and hold a reader's attention - drop them in the middle of the enormous clockwork of the Terran Empire, tie them to the cloak-tails of the decadent and highly-skilled Flandry, and keep the pace at cruising speed at all times.

Flandry emerged from his reverie. His cab was slanting toward Intelligence headquarters. He took a hasty final drag on his cigaret, pitched it in the disposer, and checked his uniform. He preferred the dashing dress version, with as much elegant variation as the rather elastic rules permitted, or a trifle more. However, when your leave has been cancelled after a few mere days Home, and you are ordered to report straight to Vice Admiral Kheraskov, you had better arrive in plain white tunic and trousers ...

Sackcloth and ashes would be more appropriate, Flandry mourned. Three, count 'em, three gorgeous girls, ready and eager to help me celebrate my birth week, starting tomorrow at Everest House with a menu I spent two hours planning; and we'd've continued as long as necessary to prove that a quarter century is less old than it sounds. And now this!

Anderson's particular gift was to create an invented, living history of his Empire, as well as the generosity to fill it with vibrant and vivid detail. Too many authors, particularly in science fiction (but also notably in recent historical fiction) treat the dramatic backdrop of their worlds as necessary evils, and parcel out the landscape in gritty, barely-digestible expository lumps that exist solely to justify the plot or move it along. The Flandry tales treat the 'backstory' as a narrative in its own right, filled with the long and fascinating digressions that readers love. Anderson's Empire is on par with the Galaxy of Asimov's Foundation, but is far more coherent, detailed and self-consistent than the "atmospheric" setting of those novels.

Hustle, bustle, hurry, scurry, run, run, run, said his glumness. Work, for the night is coming - the Long Night, when the Empire goes under and the howling peoples camp in its ruins. Because how can we remain forever the masters, even of our insignificant spatter of stars, on the fringe of a galaxy so big we'll never know a decent fraction of it? Probably never more than this sliver of one spiral arm that we've already seen....

Our ancestors explored farther than we in these years remember. When hell cut loose and their civilization seemed about to fly into pieces, they patched it together with the Empire. And they made the Empire function. But we ... we've lost the will. We've had it too easy for too long. And so the Merseians on our Betelgeusean flank, the wild races everywhere else, press inward.... Why do I bother? Once a career in the Navy looked glamorous to me. Lately, I've seen its backside. I could be more comfortable doing almost anything else.

The Rebel Worlds is a fine example of Anderson's light, fast - and sometimes wry - space opera handiwork, that can be started and finished in a lazy afternoon. The adventures of Flandry, who has been often compared to a James Bond among the stars, don't disappoint as undemanding, guilty pleasure reading.