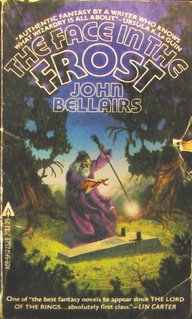

The Face in the Frost

"Unexplained noises are best left unexplained." The Face in the Frost, John Bellairs (Ace Science Fiction, 1969)

"Unexplained noises are best left unexplained." The Face in the Frost, John Bellairs (Ace Science Fiction, 1969)Sound advice, from John Bellairs' very whimsical and secretive wizard Prospero ("not the one you are thinking of, either," Bellairs tells us), to his stoic housekeeper Mrs. Durfey - and incidentally, a pretty good rule of thumb for fantasy writers in general, one that Bellairs adheres to faithfully and effectively in The Face in the Frost.

Good authors know that over-explaining is the death of storytelling, and John Bellairs was nothing if not a fellow who knew his work. He knew that readers like to use their imaginations, and despise stories that take us on a breathless, regimented forced-march. Many of us read to escape, and aren't willing to give up our time to a writer far too much in love with their own intricate plots, nor trade a mundane reality for a make-believe world that insists on controlling where our thoughts roam at all times.

The Face in the Frost, fortunately, doesn't fall into the complexity trap. It is a deeply satisfying and undemanding read. Bellairs sketches out just enough of the oddly funny and frightening world of the North Kingdom and the South Kingdom to help us form a picture, and relies on his matchless descriptive power to keep us wanting to see more. No need to lead us down the path, he simply maps it out and makes us want to follow it.

Anyone foolish enough to stand on Barren Tor in the booming wind of a certain wintry day in late October would have seen a box carriage scooting past below, like a black beetle. The Tor, a treeless 300-foot high hill shaped a little like a dog's tooth, was an isolated foothill of the unnamed range of peaks that bordered the Northern Highlands. Northerners did not name mountain ranges; they were afraid that doing so would wake the spirit of the mountains, the rock-buried elemental that had once split the Mitre, a strange double peak many miles to the south. Roger and Prospero, now many days' journey from the clockmaker's cottage, had passed the Mitre a week before: It was there they heard rumors of a War Council on the Feasting Hill.

Bellairs' storytelling gifts were many, and fully on display in The Face in the Frost, which I consider his finest book among a cohort of superb stories. He made his career as a successful children's or young adult's writer, it is true, but all of his books have the sly, clever, grown-up humor of a man who tells everyone he writes for kids, but is really writing for himself and for anyone else who wants to get lost in bramble-filled woods pursued by strange, gibbering creatures, or explore the houses of wizards with their anachronistic curios, haunted cellars and bedsteads with bassoons carved into the headposts.

Chief among his gifts is the humor Bellairs imbues in his characters, in this case, Prospero and his friend Roger Bacon (most probably the one you are thinking of), as they delve into the mystery of who is trying to kill the former through frighteningly powerful - if erratic - magic, and why.

"Well, I asked it how to make a brass wall to encircle England, and it said, 'Hah?' 'Brass wall,' I said, louder. 'B as in Bryophyta ...'"

"Bryophyta? Prospero asked.

"Yes," answered Roger testily, "mosses and liverworts."

"I hate liver," said Prospero.

"As well you might," said Roger in a quiet, despairing voice. "As well you might. But be that as it may, I spelled it out. R as in rotogravure process ..." He waited, but Prospero, who was biting down hard on his pipe to keep from laughing, did not interrupt. "... A as in Anaxagoras, S as in Symplegades, and S as in Smead Jolley, the only baseball player in history to make four errors on a single played ball.... At any rate, when I chanted the formula the next day, down by the seashore, I heard a sound like crumhorns and shawms, and behold! All of England was encircled with an eight-foot-high wall of Glass!"

"Glass? Plain, ordinary glass?"

"Yes, and not very good glass at that. Paper-thin and full of bubbles and pocks. The first boatload of Vikings that came over after the wall went up turned around and went back, because it was a sunny day and the wall glittered wonderfully. But the next day, when they came back, it was cloudy. One of them gave the wall a little tap with an ax, and it went tinkle, tinkle, tinkle, and now there is a lot of broken glass on the beach. Not long after that, I was asked to leave."

Prosper could not think of anything adequate to say, so he suggested that they break out the brandy and cigars.

Another Bellairs' touch is his longtime embrace of the old, scary connotations of magic. Mischief and horror - leavened by the hilarious or even just the buffoonish - loom large in the wizardly craft as practiced in the Kingdoms.

Prospero walked out to where the white shape was, and found that he was standing over a long flat stone, a grave marker covered with square chiseled letters in ragged rows. Some of the letters were filled with dirt, though the slab itself was amazingly clean - no bird droppings, no leaf stains or weather streaks. What the inscription said was this:

Under this stone we have placed the burnt body of Melichus the sorcerer. He did great wrong. May his soul lie here under this stone with his body and trouble us not.

"That is a terrible curse," said Prospero, looking at the quiet branches all around him. "I hope it did not come true, for his sake."

John Bellairs never achieved the fame of later authors who followed the trail he blazed - one thinks of the Lemony Snicket books, with their dark children's humor and mysterious twists, or the Harry Potter child-wizard phenomenon, that has ensnared kids and adults alike. Which is a grand pity, because his work (often illustrated by the magnificently weird Edward Gorey), surpasses both in simplicity and quality, in my opinion (and above all, in sympathy - for his characters and readers alike). Bellairs was telling stories, not building a "brand" or helping create a publishing empire.

Selfish readers (like myself) enjoy nothing better than a secret book known only to a handful of close henchmen and confidants. The knowledge that a favorite "undiscovered author" is still safe from the withering and unforgiving glare of popularity is a source of comfort and shared - if slightly guilty - delight. But Bellairs deserves far more than the relative obscurity that has been his reward up to now. I hope that when the readers of his Snicket and Potter godchildren finish those books, they'll trace their lineage and find the master in their ancestry.